Adiabatic process

In thermodynamics, an adiabatic process or an isocaloric process is a thermodynamic process in which the net heat transfer to or from the working fluid is zero. Such a process can occur if the container of the system has thermally-insulated walls or the process happens in an extremely short time, so that there is no opportunity for significant heat exchange[1]. The term "adiabatic" literally means impassable[2], coming from the Greek roots ἀ- ("not"), διὰ- ("through"), and βαῖνειν ("to pass"); this etymology corresponds here to an absence of heat transfer. Conversely, a process that involves heat transfer (addition or loss of heat to the surroundings) is generally called diabatic. Although the terms adiabatic and isocaloric can often be interchanged, adiabatic processes may be considered a subset of isocaloric processes; the remaining complement subset of isocaloric processes being processes where net heat transfer does not diverge regionally such as in an idealized case with mediums of infinite thermal conductivity or non-existent thermal capacity.

In an adiabatic irreversible process, dQ = 0 is not equal to TdS (TdS > 0). dQ = TdS = 0 holds for reversible processes only. For example, an adiabatic boundary is a boundary that is impermeable to heat transfer and the system is said to be adiabatically (or thermally) insulated; an insulated wall approximates an adiabatic boundary. Another example is the adiabatic flame temperature, which is the temperature that would be achieved by a flame in the absence of heat loss to the surroundings. An adiabatic process that is reversible is also called an isentropic process. Additionally, an adiabatic process that is irreversible and extracts no work is in an isenthalpic process, such as viscous drag, progressing towards a nonnegative change in entropy.

One opposite extreme—allowing heat transfer with the surroundings, causing the temperature to remain constant—is known as an isothermal process. Since temperature is thermodynamically conjugate to entropy, the isothermal process is conjugate to the adiabatic process for reversible transformations.

A transformation of a thermodynamic system can be considered adiabatic when it is quick enough that no significant heat is transferred between the system and the outside. At the opposite extreme, a transformation of a thermodynamic system can be considered isothermal if it is slow enough so that the system's temperature remains constant by heat exchange with the outside.

Contents |

Adiabatic heating and cooling

Adiabatic changes in temperature occur due to changes in pressure of a gas while not adding or subtracting any heat. In contrast, free expansion is an isothermal process for an ideal gas.

Adiabatic heating occurs when the pressure of a gas is increased from work done on it by its surroundings, e.g. a piston. Diesel engines rely on adiabatic heating during their compression stroke to elevate the temperature sufficiently to ignite the fuel.

Adiabatic heating also occurs in the Earth's atmosphere when an air mass descends, for example, in a katabatic wind or Foehn wind flowing downhill. When a parcel of air descends, the pressure on the parcel increases. Due to this increase in pressure, the parcel's volume decreases and its temperature increases, thus increasing the internal energy.

Adiabatic cooling occurs when the pressure of a substance is decreased as it does work on its surroundings. Adiabatic cooling does not have to involve a fluid. One technique used to reach very low temperatures (thousandths and even millionths of a degree above absolute zero) is adiabatic demagnetisation, where the change in magnetic field on a magnetic material is used to provide adiabatic cooling. Adiabatic cooling occurs in the Earth's atmosphere with orographic lifting and lee waves, and this can form pileus or lenticular clouds if the air is cooled below the dew point. Also, the contents of an expanding universe (to first order) can be described as an adiabatically cooling fluid. When the pressure applied on a parcel of air decreases, the air in the parcel is allowed to expand; as the volume increases, the temperature falls and internal energy decreases. (See - Heat death of the universe)

Rising magma also undergoes adiabatic cooling before eruption.

Such temperature changes can be quantified using the ideal gas law, or the hydrostatic equation for atmospheric processes.

No process is truly adiabatic. Many processes are close to adiabatic and can be easily approximated by using an adiabatic assumption, but there is always some heat loss; as no perfect insulators exist.

Ideal gas (reversible process)

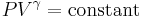

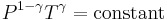

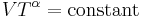

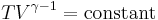

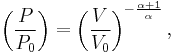

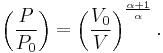

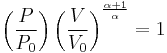

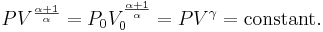

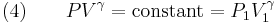

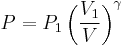

The mathematical equation for an ideal gas undergoing a reversible (i.e., no entropy generation) adiabatic process is

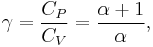

where P is pressure, V is specific or molar volume, and

being the specific heat for constant pressure,

being the specific heat for constant pressure,  being the specific heat for constant volume, γ is the adiabatic index, and

being the specific heat for constant volume, γ is the adiabatic index, and  is the number of degrees of freedom divided by 2 (3/2 for monatomic gas, 5/2 for diatomic gas).

is the number of degrees of freedom divided by 2 (3/2 for monatomic gas, 5/2 for diatomic gas).

For a monatomic ideal gas,  , and for a diatomic gas (such as nitrogen and oxygen, the main components of air)

, and for a diatomic gas (such as nitrogen and oxygen, the main components of air)  [3]. Note that the above formula is only applicable to classical ideal gases and not Bose–Einstein or Fermi gases.

[3]. Note that the above formula is only applicable to classical ideal gases and not Bose–Einstein or Fermi gases.

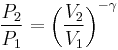

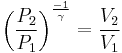

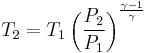

For reversible adiabatic processes, it is also true that

where T is an absolute temperature.

This can also be written as

Example of adiabatic compression

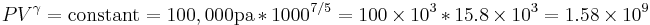

Let's now look at a common example of adiabatic compression- the compression stroke in a gasoline engine. We will make a few simplifying assumptions: that the uncompressed volume of the cylinder is 1000cc's (one liter), that the gas within is nearly pure nitrogen (thus a diatomic gas with five degrees of freedom and so  = 7/5), and that the compression ratio of the engine is 10:1 (that is, the 1000 cc volume of uncompressed gas will compress down to 100 cc when the piston goes from bottom to top). The uncompressed gas is at approximately room temperature and pressure (a warm room temperature of ~27 degC or 300 K, and a pressure of 1 bar ~ 100,000 Pa, or about 14.7 PSI, or typical sea-level atmospheric pressure).

= 7/5), and that the compression ratio of the engine is 10:1 (that is, the 1000 cc volume of uncompressed gas will compress down to 100 cc when the piston goes from bottom to top). The uncompressed gas is at approximately room temperature and pressure (a warm room temperature of ~27 degC or 300 K, and a pressure of 1 bar ~ 100,000 Pa, or about 14.7 PSI, or typical sea-level atmospheric pressure).

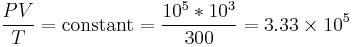

so our adiabatic constant for this experiment is about 1.58 billion.

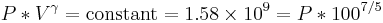

The gas is now compressed to a 100cc volume (we will assume this happens quickly enough that no heat can enter or leave the gas). The new volume is 100 ccs, but the constant for this experiment is still 1.58 billion:

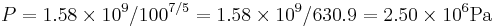

so solving for P:

or about 362 PSI or 24.5 atm. Note that this pressure increase is more than a simple 10:1 compression ratio would indicate; this is because the gas is not only compressed, but the work done to compress the gas has also heated the gas and the hotter gas will have a greater pressure even if the volume had not changed.

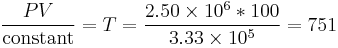

We can solve for the temperature of the compressed gas in the engine cylinder as well, using the ideal gas law. Our initial conditions are 100,000 pa of pressure, 1000 cc volume, and 300 K of temperature, so our experimental constant is:

We know the compressed gas has V = 100 cc and P = 2.50E6 pascals, so we can solve for temperature by simple algebra:

That's 751 Kelvins, or 477 °C, or 892 °F. This is why a high compression engine requires fuels specially formulated to not self-ignite (which would cause engine knocking when operated under these conditions of temperature and pressure), or that a supercharger and intercooler to provide a lower temperature at the same pressure would be advantageous. A diesel engine operates under even more extreme conditions, with compression ratios of 20:1 or more being typical, in order to provide a very high gas temperature which insures immediate ignition of injected fuel.

Adiabatic free expansion of a gas

For an adiabatic free expansion process, the gas is contained in an insulated container and a vacuum. The gas is then allowed to expand in the vacuum. The work done by or on the system is zero, because the volume of the container does not change. The First Law of Thermodynamics then implies that the net internal energy change of the system is zero. For an ideal gas, the temperature remains constant because the internal energy only depends on temperature in that case. Since at constant temperature, the entropy is proportional to the volume, the entropy increases in this case, therefore this process is irreversible.

Derivation of continuous formula for adiabatic heating and cooling

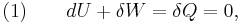

The definition of an adiabatic process is that heat transfer to the system is zero,  . Then, according to the first law of thermodynamics,

. Then, according to the first law of thermodynamics,

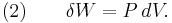

where dU is the change in the internal energy of the system and δW is work done by the system. Any work (δW) done must be done at the expense of internal energy U, since no heat δQ is being supplied from the surroundings. Pressure-volume work δW done by the system is defined as

However, P does not remain constant during an adiabatic process but instead changes along with V.

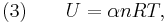

It is desired to know how the values of dP and dV relate to each other as the adiabatic process proceeds. For an ideal gas the internal energy is given by

where  is the number of degrees of freedom divided by two, R is the universal gas constant and n is the number of moles in the system (a constant).

is the number of degrees of freedom divided by two, R is the universal gas constant and n is the number of moles in the system (a constant).

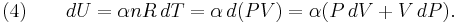

Differentiating Equation (3) and use of the ideal gas law,  , yields

, yields

Equation (4) is often expressed as  because

because  .

.

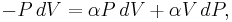

Now substitute equations (2) and (4) into equation (1) to obtain

simplify:

and divide both sides by PV:

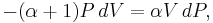

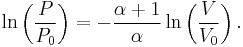

After integrating the left and right sides from  to V and from

to V and from  to P and changing the sides respectively,

to P and changing the sides respectively,

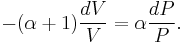

Exponentiate both sides,

and eliminate the negative sign to obtain

Therefore,

and

Derivation of discrete formula

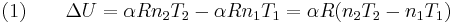

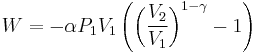

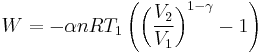

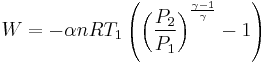

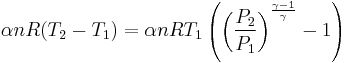

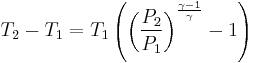

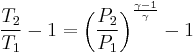

The change in internal energy of a system, measured from state 1 to state 2, is equal to

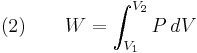

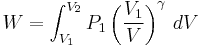

At the same time, the work done by the pressure-volume changes as a result from this process, is equal to

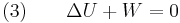

Since we require the process to be adiabatic, the following equation needs to be true

By the previous derivation,

Rearranging (4) gives

Substituting this into (2) gives

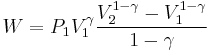

Integrating,

Substituting  ,

,

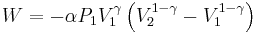

Rearranging,

Using the ideal gas law and assuming a constant molar quantity (as often happens in practical cases),

By the continuous formula,

Or,

Substituting into the previous expression for  ,

,

Substituting this expression and (1) in (3) gives

Simplifying,

Simplifying,

Simplifying,

Graphing adiabats

An adiabat is a curve of constant entropy on the P-V diagram. Properties of adiabats on a P-V diagram are:

- Every adiabat asymptotically approaches both the V axis and the P axis (just like isotherms).

- Each adiabat intersects each isotherm exactly once.

- An adiabat looks similar to an isotherm, except that during an expansion, an adiabat loses more pressure than an isotherm, so it has a steeper inclination (more vertical).

- If isotherms are concave towards the "north-east" direction (45 °), then adiabats are concave towards the "east north-east" (31 °).

- If adiabats and isotherms are graphed severally at regular changes of entropy and temperature, respectively (like altitude on a contour map), then as the eye moves towards the axes (towards the south-west), it sees the density of isotherms stay constant, but it sees the density of adiabats grow. The exception is very near absolute zero, where the density of adiabats drops sharply and they become rare (see Nernst's theorem).

The following diagram is a P-V diagram with a superposition of adiabats and isotherms:

The isotherms are the red curves and the adiabats are the black curves.

The adiabats are isentropic.

Volume is the horizontal axis and pressure is the vertical axis.

See also

- Cyclic process

- First law of thermodynamics

- Heat burst

- Isobaric process

- Isenthalpic process

- Isentropic process

- Isochoric process

- Isothermal process

- Polytropic process

- Entropy (classical thermodynamics)

- Quasistatic equilibrium

- Total air temperature

- Adiabatic engine

- Magnetic refrigeration

References

- ^ http://buphy.bu.edu/~duffy/semester1/c27_process_adiabatic_sim.html

- ^ http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/adiabatic

- ^ http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/thermo/adiab.html

- Silbey, Robert J.; et al. (2004). Physical chemistry. Hoboken: Wiley. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-471-21504-2.

- Broholm, Collin. "Adiabatic free expansion." Physics & Astronomy @ Johns Hopkins University. N.p., 26 Nov. 1997. Web. 14 Apr. *Nave, Carl Rod. "Adiabatic Processes." HyperPhysics. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2011. <http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/thermo/adiab.html>.

- Thorngren, Dr. Jane R.. "Adiabatic Processes." Daphne – A Palomar College Web Server. N.p., 21 July 1995. Web. 14 Apr. 2011. <http://daphne.palomar.edu/jthorngren/adiabatic_processes.htm>.